In the months of July and August 2022, Senegal and Kenya will hold their general elections. However, the big question remains: Where do Senegalese and Kenyan women stand on their quest to parliamentary mandates and political offices?

Recent statistics from Afrobarometer, the number of women in politics, academia and in business has been slowly but steadily increasing on the African continent over the last two decades. At a quick glance, this could paint a picture of success in gender equity. However, that is not the case.

In the months of July and August 2022, Senegal and Kenya will hold their general elections. However, the big question remains: Where do Senegalese and Kenyan women stand on their quest to parliamentary mandates and political offices? Are legal and policy frameworks that the respective governments have put in place to enhance gender equality in politics yielded any fruits?

Senegal

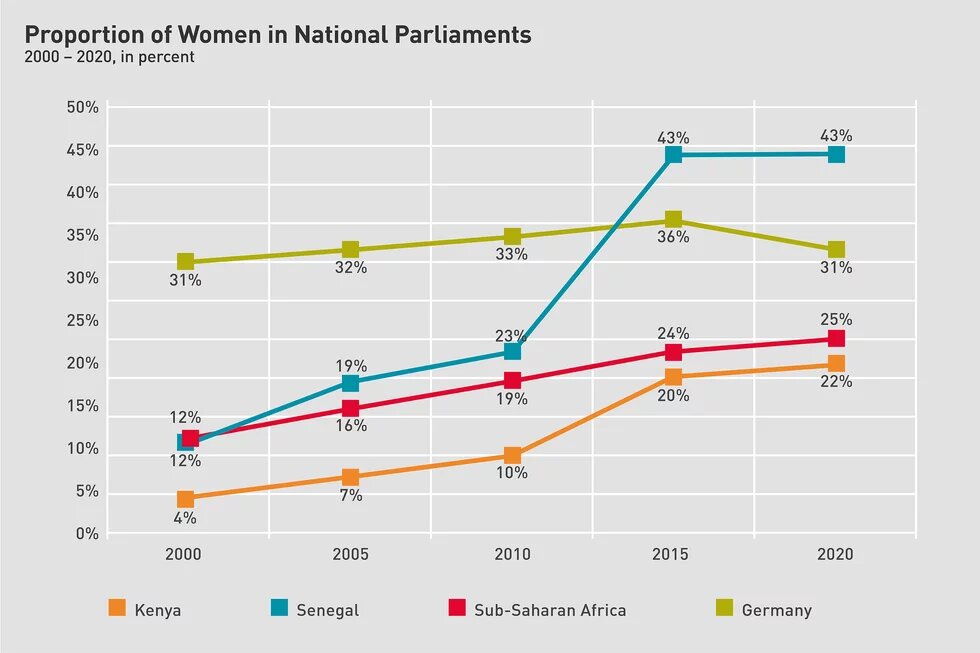

On 31 July 2022, Senegalese will elect a new parliament (Assemblée Nationale) for the next five years. In the current legislative period (2017-2022), 71 out of 165 MPs are women. This is the third parliamentary election since adopting the parity law in 2010, which has led to a considerable increase in the proportion of women in parliament. Currently, Senegal ranks 4th on the African continent with 43 per cent women in the national parliament - after Rwanda (61 per cent), South Africa (47 per cent) and Namibia (46 per cent) and 19th in the world. In comparison, Germany is in 44th place as of May 2022.

Effectiveness of the parity law and its limits

The parity law ("loi sur la parité"), which came into force in 2010, is an essential step towards achieving democracy and equality among the Senegalese. This law, stipulates that half of the candidates on the electoral lists of each party must be women. The law has led to a significant increase in the number of women in parliament. At the same time, the nomination quotas mean that political parties have to pay attention to the gender agenda. Nevertheless, only a few women make it into leadership positions within parliamentary bodies. Currently, only two of the fourteen parliamentary committees are chaired by women. There is also still great inequality in the parliamentary presidium, as men still occupy the strategically important positions. In addition to a more gender-equal distribution of the mandates themselves, equal representation in the parliamentary groupings is therefore crucial in attainment of affirmative action within parliament.

Despite there being a law formulated a decade ago on affirmative action, political party’s leadership structure continues to be dominated by male elites who control the entry pass for candidates. With such a scenario, the woman’s role in most political parties has been reduced to mobilisation and campaigning for men candidates rather than vie for leadership positions. This development of a gendered division of labour in politics reveals and perpetuates the persistence of male dominance mechanisms.

For instance, the local elections held in January 2022, to elect members of the municipal councils as well as the mayors of Senegal, the Parity Act did result to more women being represented in local assemblies. Nevertheless, among the 557 mayors elected nationwide with only 18 women. This represents a meagre 3.2 percent number of women mayors.

Therefore, compliance with the parity law remains a fundamental issue in this year's parliamentary elections. For example, the lists of the two major political party alliances, BBY (Benno Bokk Yaakaar - the ruling coalition of President Macky Sall) and YAW (Yewwi Askan Wi - the opposition alliance), are facing disqualification from the parliamentary elections for failing to comply with the provisions of the Parity Act.

The parity law is however, still very unpopular amongst some conservative and religious members of the society. In some rural parts of the Touba, which is second most populated Senegalese city after Dakar such as, the holy city of the Muslim Mourid Brotherhood, the municipality's list of candidates for the local elections did not comply with the provisions of the parity law. No single woman was nominated for the elections. The list was nevertheless declared valid by the Minister for Interior. The reason for this is probably the considerable influence of the Mourid Brotherhood, which extends into the political institutions of the capital.

Indeed, the representation of women to political offices indicates that parity law is only a first step that paves the way for women to enter politics. The law’s effectiveness, however, depends on overcoming political, cultural and religious hurdles. Senegalese sociologists and politicians emphasise that the general acceptance of women in leadership positions is still alien. This should not be the norm.

Women politicians' commitment to women's issues

With the increase of women in parliaments, the number of explicitly feminist legislators is also rising with most of them linked to feminist organisations and networks. Ndeya Luci Cissée, who is the current Vice President of parliament and former President and active member of the Senegalese Women's Council (COSEF) is an illustrative example.

There are benefits an tangible successes of women’s involvement in politics and women's organisations. For instance, the January 2022 law criminalising rape and paedophilia is a perfect milestone that has put in legal frameworks that allows harsher sentences for acts of gender-based violence.

Some politicians vying for seats however are shying off from supporting the gender parity law as they fear to be victimized by the society that is yet to embrace gender equality. For instance, demands on issues such as abortion, polygamy and family law reforms tends to be a hot issue during the campaigns with culture and religion playing a major role. It can be observed that - as in many countries around the world - anti-feminist actors are positioning themselves offensively, whose aim is, among other things, to sabotage developments towards more gender equality. Feminist policies would, according to them, pose "a threat" to the Senegalese family model.

Kenya

Defining election in Kenya: How is the gender score card?

On 9 August 2022, Kenya will hold six elections in parallel: In addition to the presidential election, the Senate and Parliament, as well as County Parliaments (local parliaments), governors and women's representative bodies of the 47 counties will be elected. One would imagine there are any opportunities for women to be elected to political office, but what are their chances?

Since the last elections held in 2017, 21.8 percent of national parliamentary seats are held by women. This places Kenya 106th in the international ranking of women in national parliaments. In the Executive arm of the government, only seven out of 21 ministries are headed by women. For the first time this term, women were elected as governors and senators. The late Joyce Laboso, Anne Waiguru, Charity Ngilu, Margaret Kamar, Dullo Fatuma Adan and Susan Kihika made history by dethroning men. Another first was the election of women candidates who contested independently.

Despite an increase in the proportion of women, the necessary progress was not made to achieve the constitutionally mandated minimum of 33 per cent of women in elective offices.

The 2010 Kenyan Constitution established a gender quota. This means "no more than two-thirds of elected public bodies shall be composed of persons of the same sex.”

Twelve years later, the Kenyan Parliament and government organs - despite six court orders - are yet to pass a law that will fully implement Article 27 of the constitution. Therefore, the implementation of the two-thirds rule has remained one of the key demands of women MPs during the last two election periods. To date, a law has failed due to the resistance of the majority male parliamentarians.

Women also face a number of other obstacles on their way into political office. These include insufficient political support from their parties, especially during primaries, lack of funding, gender-based violence against women politicians, gender stereotypes and patriarchal structures in society.

For instance, when women vie for elective political positions, they face verbal sexism, online gender based violence and risk physical attacks. In the 2013 and 2017 elections, there were high levels of sexual and gender-based violence against women politicians.

After the 2013 elections, women candidates reported harassment, intimidation and violence during the campaign. Case in point is Janet Chepkwony, a former candidate for a member of county assembly position in, Nandi County said. "I received death threats, while some supporters were physically abused or intimidated," MP Millie Odhiambo's house was also burnt down just a day after her political party nominated her.

These tactics intimidate and discourage women politicians and candidates from participating in active politics. Women politicians and the state’s gender commissionare pushing for the state and political parties to enact measures and policies to deter and punish perpetrators of online and physical gender-based violence. It remains to be seen how effective the measures will be before the August 2022 elections.

Patriarchal language to delegitimise female leadership

Women who venture into politics are judged mainly by their outward appearance rather than their substantive contributions and qualifications. Some of the campaign mudslinging tactics used by women candidate’s opponent and their supporters include; body shaming, sexist and misogynistic remarks on their marital status especially if not married. These factors are used effectively by male candidates to denigrate women candidates’ hence legitimising male dominance.

Female parliamentarians, however, are increasingly resisting sexist questions during media interviews. Questions such as “how do you balance family duties and politics” has been frowned upon by some women politicians. The civil society organisations are also, increasingly denouncing male politicians who make sexist comments in public about women. In addition, trainings for journalists on gender-sensitive language and stereotypes have increased in recent past.

The fight against patriarchal and women-discriminatory language is a long one. Much needs to be done, both in terms of legislation and from a human rights perspective, to improve gender equality in Kenya during the election slated for 9 August 2022 and thereafter.

On the other side, numerical representation by women in politics does not guarantee the creation or advocacy of an equal political system. Women still have challenges accessing political offices. Moreover, the successes of some women in leadership positions such as in the legislative does not reflect the social realities faced by a large number of African women such as inequalities, discrimination and obstacles in other areas of their life.

In other words, more gender parity in parliaments is a good start and a lever for change however; political offices and economic and social leadership positions must also be filled in a more gender-equal way. Hurdles to equality and political participation are not only legal but also social-cultural. As a result, solutions to overcome them require targeted efforts in challenging patriarchal socialisation of men and women to build new, equal structures. Only in this way can a balanced power relationship between men and women be achieved.

To echo words of Kenyan professor Maria Nzomo: "Increasing women's representation does not automatically change the dominant male culture in government structures or the unequal distribution of political power between men and women." Unfortunately, her words seems to remain valid. Much remains to be done for equal participation in political power arena.

This article was first published on boell.de.